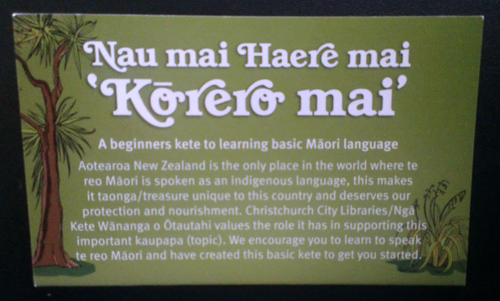

Kete distributed by Christchurch City Libraries during the Maori Language Week

Ever since the country started marking the Māori Language Week in 1975, the cultural and historical argument to preserve the language has held its ground. It’s time to introduce the economic element into it as well.

Endangered Language Alliance (ELA) – a non-profit based in New York and working towards preserving the world’s linguistic diversity – outlines three fundamental reasons to save a language from dying: human rights, communal identity and science. What can be added in te reo Māori’s case is the economic benefit that New Zealand will have if this 800-year-old treasure flourishes here again.

Economics of collective knowledge

First and foremost – and in the domain where some work has already started – is te reo Māori’s extensive database of weather and climate of New Zealand.

The National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research (NIWA), a crown research institute established in 1992, says, “Over the centuries, Māori have developed an extensive knowledge of weather and climate. The lessons learnt have been incorporated into traditional and modern practices of agriculture, sailing, fishing, and conservation.”

“NIWA’s research and development unit, in collaboration with iwis from across New Zealand, has initiated a project to explore this traditional knowledge, and link events in the natural world to the forecasting of weather and climate,” adds the institute.

And this is not unique to New Zealand’s oldest language.

As Judith Thurman points out in her brilliant article in The New Yorker, “The taxonomies of endangered languages often distinguish hundreds more types of flora and fauna than are known to Western science.”

“Take for example, Polynesian herbal doctors of Samoa who had an extensive nomenclature for endemic diseases; or the Haunóo tribe of the Philippines which has forty expressions for types of soil; or the forest-dwelling healers of South-east Asia who have identified the medicinal properties of some sixty-five hundred species,” she adds.

A case in point – where Māori knowledge had helped New Zealand trade – was the country’s flax business.

Flax – one of the New Zealand’s most distinctive native plants – was used by Māori since 1200s as raw materials for clothing and home-ware, as well as for medicinal purposes.

When Europeans arrived in the 1700s, they expanded the usage to rope-making to be fitted in sailing ships, among other uses. It grew to an extent that a flax fibre trade started between New Zealand, Australia and Britain, which peaked in the 1830s.

In a nutshell, Māori’s knowledge of flax and its subsequent enhancement by Pākehā can be touted as probably one of the first examples of overseas trade by this great trading nation.

Some might say that whatever scientific knowledge te reo Māori had incorporated since 1200s, western science has already made use of it in the last 200 years. But recalling how te reo Māori and its usage was actively discouraged in the country till few decades ago, it’s quite plausible that we will discover newer knowledge as more and more people learn the language and revisit its literature, stories, and events.

Economics of communal identity

Another economic benefit is the role te reo Māori can play in helping offenders identified with Māori ethnicity reintegrate into the society.

The statistics show that almost 50 percent of our prison population is identified as Māori. This is well over the proportion of people with Māori ethnicity in the country’s population, which is just 15 percent.

Most of these offenders are victims of alcohol and drug abuse themselves, who need societal and systemic support to come back to the mainstream.

And as pointed by ELA, “The value of rooted identities to individual and communal health is only now beginning to find wider acceptance among scientific circles. Studies in both the United States and Australia have shown significant correlations between increased use of indigenous language and avoidance of drug and alcohol abuse. What is the reason behind this? It is very likely that the very act of speaking one’s traditional communal language is living proof that one does not belong to a vanquished people.”

ELA refers to a 2011 Australia study of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youths which linked “speaking an indigenous language to youth well-being”.

The US, in fact, has used “American Indian cultural activities in substance abuse prevention programs as part of the indigenous cultural renaissance that has been under way in tribal communities since the late 1960’s”, noted authors Ruth Sanchez-Way and Sandie Johnson in their paper published by the National Criminal Reference Service (NCJRS) of America.

Thus, as it had done in other countries, wide use and encouragement of te reo Māori among offenders identified as having Māori ethnicity will certainly help Corrections in achieving its goal of reducing re-offending by 25 percent by 2025, which in turn has tremendous economic benefits to the society.

Economics of multilingualism

Finally – and it’s a no-brainer really because various studies have proved this in the last few decades – multilingualism improves creativity, cognitive development, and problem-solving abilities in humans.

Thus, when Jeffrey Kluger, senior editor at the Time magazine, writes, “New studies are showing that a multilingual brain is nimbler, quicker, better able to deal with ambiguities, resolve conflicts and even resist Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia longer,”; we can extrapolate his argument and infer that a future New Zealand, where every kid learns at least two languages – English and another of his or her choice (preferably Māori because of its other benefits and relevance here, but may be Chinese, German, French etc.) – will be a country of more creative and more healthy citizenry.

This will mean more entrepreneurship, more leaders, more innovation, more businesses, i.e. an improved economic scene overall.

What we will save in reduced healthcare costs due to less instances of mental health diseases will be an added economic advantage.

-Gaurav Sharma

(this article was originally published in The Migrant Times here)